words by Jane Chin

Those of us "mature" climbers between the ages of late 30's to mid 50's who fell in love with climbing are made aware of how our bodies respond to this sport -- often painfully aware. I'm not talking about people who climb well into their 50s and 60s but started out in their teens or 20s. I'm talking about people like my husband and me, GenX'ers who started climbing almost 5 years ago. I agreed to a guest pass at a local climbing gym, and I have been climbing ever since.

My husband and I joke about ibuprofen being a food group when we first started climbing because of how sore we'd get, although my husband goes for naproxen (brand name: Aleve) while I prefer ibuprofen (brand name: Advil). "Hard climbing" for 20-somethings may mean working out 5 times a week in between outdoor sessions. Getting on the walls more than 2-3 times a week -- depending on the week -- is a challenge for my body. My brain desperately wants to climb more often, but my body lets me know when I've pushed too hard. In fact, my joints, muscles, and nerves let me know that I've ignored my limits.

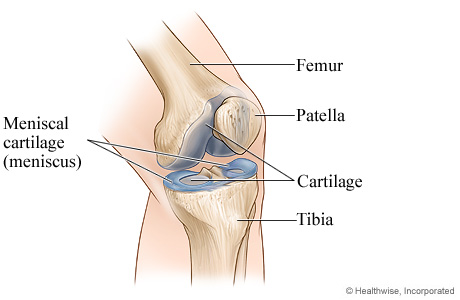

We mature climbers may have all the "will" in the world, but we have no control over the reality of decreasing cartilage volume from age. Cartilage is the elastic connective tissue that covers, pads, and protects our body. It is more flexible than bone but more rigid than muscle, making this a critical "connector" in our anatomy. The presence of cartilage provides friction-buffering and lubrication between our joints, especially during high mechanical "shear stress" situations that occur when we climb. Cartilage gets worn and frayed with age. Those of us who have ever sustained any cartilage injuries already know that cartilage does not have blood vessel supplies, which means recovering from cartilage injury can be a difficult, painful, and lengthy process. In some situations, surgery may be the only option (besides not climbing, which is obviously not an option).

Many of us older climbers may have osteoarthritis (OA), which is a degenerative joint disease that "naturally" occurs with age. Age-related OA typically affects joints in the hands, hips, knees, and vertebrae/spine - that's right - all the joints we use for climbing! Genetics can play a role for some younger climbers, where they may experience OA in certain parts of their bodies, such as the neck. Correct climbing technique becomes important to reduce excess strain on joints. Strong core muscles means off-loading from joints, which reduces risks of joint injuries. The good news is that our core muscles are highly trainable even with age! Most of us equate "core" with "abdominals" but core actually comprises of pelvic floor muscles, spine, and even diaphragm. Note: Stop walking by and ignoring Sender One's "core class" announcements and actually sign up for a class!

A good climbing habit is more about accepting that the body needs rest rather than pushing my comfort zones. I find that my personal recovery time is at least 2-3 days between hard climbing sessions. Everyone's recovery time is different: pay attention to your body's recovery rhythms. The upside of aging for many of us may be the accumulation of "wisdom and experience", but the downside is that we have also accumulated injuries over decades. Our bodies "remember"! Not only have I seen flare ups from old injuries from martial arts in my 20s, I am still prone to the same "overuse" injuries that all enthusiastic climbers can face. A survey of climbers in British Indoor climbing gyms showed that overuse injuries account for more than 80% of climbing injuries. Even the "comforts" of an indoor climbing environment can lure climbers to ignore their physical limits and tempt them to take risks like repetitively straining on small crimpy holds! Here's a guide to help with "prehab" and injury prevention.

Even though I must show restraint to ensure that I can climb for a long long time, I continue my love affair with climbing. Climbing provides strength-based training that not only helps maintain my bone density, but improves my overall physical confidence. I get excellent cardiovascular benefit when I scale up a speed wall or do laps on top rope. Climbing truly focuses my mind and gets me "in the zone". Climbing is my moving meditation.

Citations:

Rock climbing injuries. MD Rooks. Sports Med. 1997 Apr;23(4):261-70.

Indoor rock climbing: who gets injured? DM Wright et al. Br J Sports Med 2001;35:181-185.